Today we deal with the world of improvement measures and show you two different methods for their design and implementation. The inclusion of the right group of employees in the development of improvement measures and the way in which changes are communicated are critical factors in convincing the workforce of the measures and thus laying the foundation for the success of the transformation initiative.

Only in the rarest of cases does the bitter end come completely unexpectedly for companies. De facto, several employees in different positions usually know where the problems lie or which potential lingers without realization. Nevertheless, the identification of problems is usually easier than the development of suitable improvement measures. Quickly one can lead to the next and one stands avoidably "spontaneously" before the pile of broken glass.

Nokia's former CEO Stephen Elop offers a bitter example. In tears and at the press conference that announced Nokia's sale to Microsoft, his meanwhile famous words were heard: "We didn't do anything wrong, but somehow, we lost." The question immediately arises: what could Nokia have done better? What measures should they have taken?

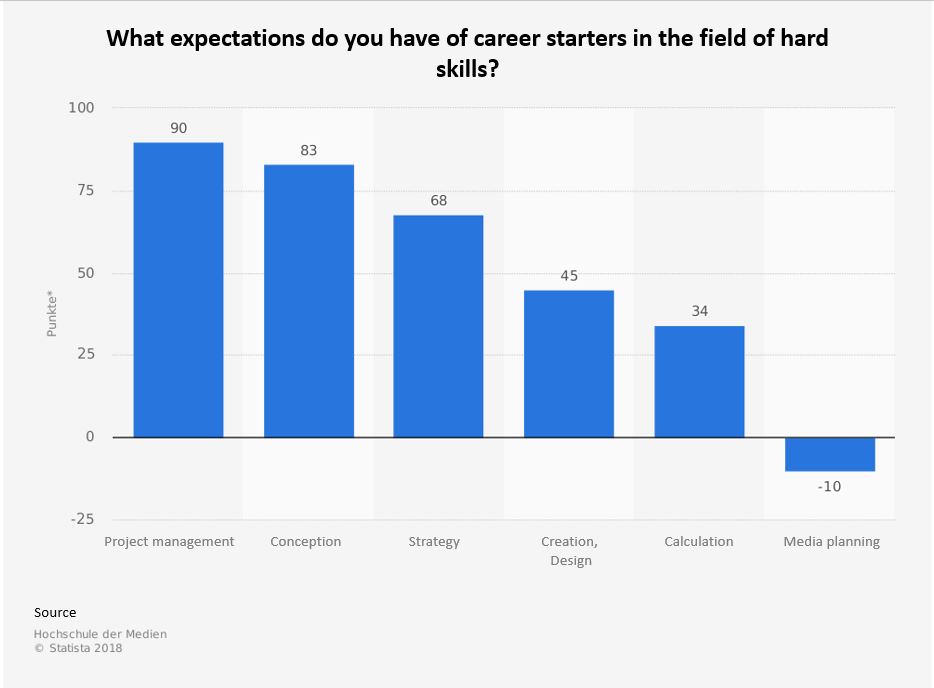

Companies expect their employees to be able to organize and manage measures

Unfortunately, however, there is no ideal way to develop improvement measures. However, a very rough distinction is made between top-down and bottom-up approaches - and any hybrid form is also conceivable. As extreme points, two exemplary measures can be used well to better understand when which approach can be useful: The (unfortunately) classic downsizing and the mostly difficult sales measure.

Top-down measures with downsizing as an example

The top-down approach means that projects, measures or changes are planned by top management. The implementation takes place in the company hierarchy from top to bottom: Managers assign the tasks to their employees, which are then executed. But when is this management style the right choice for improvement measures?

Every company will be interested in hiring the best people. However, it is also common for a wave of employees to be confronted en bloc with the search for a new job. This can have industry-specific reasons (e.g. in the German press), but can of course also be company-specific (e.g. at Opel).

Downsizing - Popular instrument in a first-aid kit for troubled corporations

Controlling and consultants have a simple game in the causal determination of the possible improvement potential of downsizing measures: Price times quantity. Perhaps possible severance payments or process costs still have to be considered as margin dampers. That's it. All this, of course, only under ceteris paribus conditions.

Let's be honest, if a consultant has to visit a new client every two months and has to search for upside-downs in the profit and loss account under high time pressure, it's logical that everyone first looks at the biggest cost block of all, right? Why this is not necessarily the right way, what consequences far-reaching layoffs have and what alternatives there are to downsizing, we will shed more light on here.

In most cases, downsizing is aimed at directly improving liquidity. The procedure for a wave of terminations is also relatively clear. Once it has been determined who can or should be dismissed, the dismissal is discussed and the potential difficulties associated with the dismissal, including the rat tail, are released. The downsizing measure can therefore not only be quantified very easily, it can also be planned without much intervention by employees outside Controlling and management. It is therefore usually a top-down measure.

We do not want to suggest in the slightest that the emotionally difficult downsizing measures can be carried out "simply". Rather, it is important to understand that they tend to be planned by individual decision-makers at the top-down management level. Other examples of typical top-down measures are building strategic alliances, reducing investments or moving to new premises.

Bottom-up measures using sales growth as an example

In the bottom-up process, changes start at the lowest hierarchical level and are carried through the company from bottom to top. The procedure is decentralized and is based on the initiative of employees who are not at the management level of the company. The technical expertise of the employees is decisive for project planning and the flow of information is largely upward from a hierarchical point of view. But how can managers tell that changes should be made in this way?

Measures that are aimed at a substantial improvement in sales and whose objectives should be achievable are predestined for bottom-up planning. In the course of digitalization, the introduction of an online shop can be cited as a prime example. Management and controlling only rarely have the necessary know-how to plan and track the development of an online shop top down. Rather, the know-how among the employees is usually sought - and if not found sufficiently - supplemented by external agencies or consultants.

Furthermore, it is very difficult to quantify the measure. It may still be possible to estimate how much the development will cost. However, it is very difficult to estimate the expected impact on sales and, above all, to track it causally. Is sales increasing because of the new online shop or because the economy is picking up? Or both? Do other factors come into play?

When planning, it is important to identify a construct of value drivers that at least indirectly makes an assessment possible. For example, online sales based on total sales, coupled with a growth rate, can give a better indication of the performance of the shop than online sales alone. The only remedy here is a rolling bottom-up planning that draws on the know-how of the employees at the front. This applies in principle to measures that deal with the optimization of (core) processes or the product portfolio, require special specialist knowledge (e.g. IT projects as well as production and procurement measures) or are intended to identify possible new innovation drivers in the company.

Drawbacks

While both forms of management have advantages for certain change measures, the difficulties with both approaches cannot be dismissed either. In the top-down process, communication of clear expectations across several levels often fails, which can dilute the original goal. But when there is clear communication, employees at lower levels of the hierarchy may feel controlled or constrained by rigid instructions. At the top, time bottlenecks can occur and at the bottom of the pyramid, motivation can drop because employees do not feel valued for their expertise. In the worst case, mere instructions from above can lead to resistance.

Bottom-up approaches are often seen as a solution here, but they present their own challenges. Although employees have expert knowledge, this often prevents them from thinking across departments or company-wide - projects cannot unfold beyond a small area of influence without the influence of management levels. Without the transformation driver from above, employees may also lack the incentive to leave their own comfort zone through a major transformation project or even to question their own operational existence.

Are hybrid styles the solution?

However, top-down and bottom-up approaches with their integral advantages and disadvantages cannot be treated exclusively or even negligently. A proven approach is the combination. Management, strategists, controlling and consultants can, for example, concentrate on the often very complex analysis of the current situation in the first step. A common analysis includes the financial, asset and earnings situation of the company over the last few years up to the current point in time. Coupled with a market and competition analysis, conclusions can be drawn on acute need for action, medium-term and long-term improvement potentials. Falconistas usually already use Falcon in this situation and track their rough project structure including goals in Falcon's project tree and measure profiles.

The next step is to consider which of the workforce is most likely to have the necessary tools to detail and implement the measures. The top-down analysis can now be supplemented by bottom-up detailing (who does what when and what should be done when) by suitable employees. In Falcon it is enough to assign a responsible person to the measures and off you go.